Know Before You Go: Emma By Kate Hamill

- Meredith Taylor Ammons

- Nov 30, 2022

- 5 min read

PlayMakers Repertory Company's current production of Emma comes in a long line of book-to-stage adaptations by Kate Hamill. She already has two previous Jane Austen adaptations under her belt: Sense and Sensibility was published in 2014, and Pride and Prejudice, published in 2018. Hamill’s Sense and Sensibility was part of the 2017/2018 season at PlayMakers Repertory Company. Hamill’s first Austen adaptation, Sense and Sensibility, was much closer to the original novel, adding a few modern dance breaks and the late Mr. Dashwood's “body” falling from the ceiling. Hamill’s Emma turns the eccentricities up to 11, which results in a farcical retelling of a classic work that can easily be digested in two and a half hours.

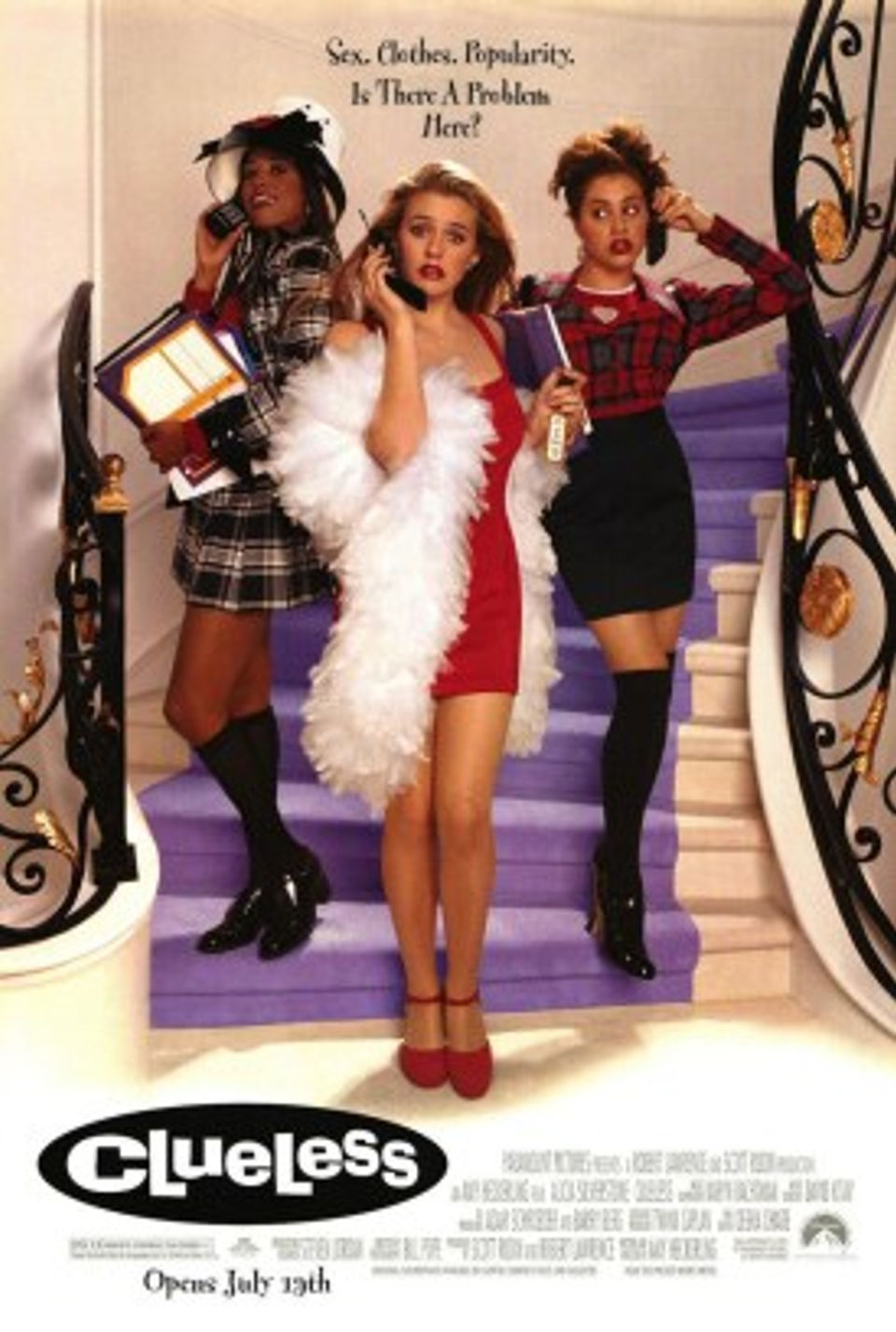

Emma by Kate Hamill is not your classic Jane Austen adaptation by any stretch of the imagination. In fact, this adaptation is more akin to Fire Island, Clueless, and Bridget Jones’s Diary. Like this play, these adaptations work as a gateway for younger audiences to be introduced to Jane Austen’s stories more than a line-by-line accurate retelling. Like those adaptations, Hamill uses modern music, modern props, and modern costuming to tell a classic story. However, this adaptation is most reminiscent of Netflix’s 2022 adaptation of Persuasion, using modern vernacular and morals within the regency setting.

The set of this production looks like Emma created it to be her perfect little world. The main stage looks like a classic fairytale illustration encased in a frame anointed with a giant E for Emma. To help the audience better understand where each scene takes place without drastic set changes, the primary locations from Hartfield to the Bates’ house are created in miniature and lit when the scene is placed there.The floor of the thrust stage is painted to look like a symbolic chessboard that Emma uses in her matchmaking plots with her friends and family as pawns.

Hamill uses Jane Austen’s story as a base on which to present modern problems. This makes sense for this production because many of the conflicts of Jane Austen’s heroines such as finding a match and getting rejected at a ball are not as readily relatable for unfamiliar modern audiences. The cast is made up of 10 high-energy actors. The tone for most Austen adaptations is usually subdued and elegant; it was quite a change of pace to see high-energy farcical acting. All of the characters are double- or triple-cast except Emma and Mr. Knightley. It was truly amazing seeing these actors inhabit such different roles. Sometimes, they would have a quick change within the same scene. And seeing the same actor portray Frank Churchill and Robert Martin, for example, has the potential to shed new light on how we read those two characters.

Because of these reductions, every single character and plotline is either tweaked, changed drastically, or omitted entirely. For example, in this adaptation, Emma is extremely educated on a variety of subjects instead of being a dilettante, Jane is already a governess, and Ms. Bates runs a school. Similar to 2022’s Persuasion, this change gives the women in the story much more agency as well as chances to show their true frustrations about their current position in society that would not be permitted in the Regency Era. For instance, Jane is the one constantly rejecting Frank’s advances and Mrs. Weston has a speech defending Emma by reminding Knightley of the social restrictions Emma faces.

This may result in a streamlined story with a smaller cast list; however, this adaptation takes away the many complexities of well-known characters that fit into a perfected puzzle and tries to move the pieces around to make an alternative picture. For example, in the novel, the most redeeming qualities of Emma we get to see are through her relationship with her father. However, since Mr. Woodhouse is only really talking about gruel for the entire play and not Emma’s importance to him, we lose that vulnerability.

Hamill’s Emma even borrows Anne Elliotts’s fourth wall breaks reminiscent of Amazon’s Fleabag. This style of writing allows the audience to be caught up on the backstory and what the character is currently feeling. It is so similar that the love interests of our main leads in Emma and Fleabag are the only ones that can see through the fourth wall.

However, this is done in completely different ways. Fleabag is a show built on fourth-wall breaks. The audience grows to love Fleabag because they feel like she is letting us in on her most intimate thoughts even mid-conversation. No one notices her speaking to us through 80% of the series. It is used not only for background information but also for dramatically-ironic humor. When The Priest looks at the camera for the first time, it is jolting because it is out of left field and we feel like the bubble we created with Fleabag has been popped. It is telling the audience that someone noticed her as a person and is seeing through her facade. It symbolizes that he is perfectly matched with her but also shows that she is using fourth wall breaks as a coping mechanism because she feels like the world isn't listening to her.

In this production, Emma is the narrator telling us her story but it's mostly in monologue vignettes explaining the background or talking about the director or PlayMakers Repertory Company. It is never really used for funny asides except for yelling at the audience for not telling her what is going to happen or saying this is different from the novel. Knightley sees through the facade the whole time. So there isn’t the same impact. The device is more symbolically used to show Emma’s lack of control over Knightley in creating her perfect world. Like Emma, he can speak with the audience; however, other characters ask who she is talking to in certain scenes.

Coincidentally, Emma and Fleabag have monologues about how powerless and isolating they can feel in their society, especially as a woman in their 20s. Where these two differ is Fleabag’s monologue is a desperate plea to a loan officer after she has lost all of her relationships with her family, had the two people who mean the most to her die, and struggled to run a failing business. There are higher stakes at hand.

Emma’s monologue is screamed at Ms. Bates about how Emma can’t understand how Ms. Bates can be happy with a mediocre school and a poor living situation as a spinster. Emma still has power in some ways. She still has money, people who love her, and no pressure to marry. She is stuck in her small society and her society sees her as only worthy of running a household. This is a frustrating situation, but not as devastating as Fleabag's predicament.

Kate Hamill’s Emma stretches the idea of literary adaptation beyond its normal scope. This production shows how Jane Austen’s work can still be used to hold a mirror to our current society, and reminds us how many different stories Austen can be made to tell.

I had the pleasure of seeing this during the holidays in Minneapolis and was entranced! I walked away feeling that if Jane was born in the late 20th century, this is the play she would have written. I adored it!